What Is the Price of Freedom Within the East African Community?

- Kizito Enock

- Jun 1, 2025

- 21 min read

Updated: Jun 2, 2025

The East African Community (EAC) was founded on promises of economic integration, shared prosperity, and respect for fundamental principles such as good governance and human rights. Yet a stark reality has unfolded across member states over the past decade: the price of exercising basic freedoms including speaking out against authorities or mobilizing politically can be extraordinarily high. From Uganda to Tanzania and even Kenya, opposition figures, activists, and journalists have faced unlawful arrests, torture, enforced disappearances, and even cross-border abductions. These abuses, documented by human rights groups, violate national laws and international norms, raising questions about the commitment of EAC governments to the rule of law and the rights of their citizens.

Reflecting from 2015 to 2025, all three countries have witnessed escalating crackdowns on dissent. In Uganda and Tanzania nations long dominated by entrenched ruling parties opposition leaders have been jailed, exiled, or even physically attacked with impunity. Kenya, while touted as a relatively freer democracy, has also seen episodes of deadly police repression and is now implicated in transnational repression – cooperating in the unlawful rendition of dissidents beyond its borders. This investigative report examines how the fundamental freedoms of expression, assembly, and opposition politics have been curtailed across the region, and how recent events like the brazen abduction of a Ugandan opposition leader from Kenyan soil illustrate a dangerous new phase of regional collaboration in repression. We draw on reports from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the United Nations, and other sources to document a pattern of political persecution and human rights abuses that threatens to undermine the EAC’s founding principles.

Uganda: Crackdown at Home and Across Borders

Uganda’s President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni Tibuhaburwa, took over power since 1986, has long relied on heavy-handed tactics to stifle any challenge to his rule. Opposition politicians and their supporters have endured years of harassment, arbitrary detention, and violence. In recent times, these tactics escalated to an unprecedented level: transnational kidnapping. In a shocking violation of international law, on November 16, 2024, Ugandan opposition leader Dr. Kizza Besigye was abducted by armed men in Nairobi, Kenya, and forcibly transported across the border to Uganda. For four days, Besigye was held incommunicado, his whereabouts unknown, until he reappeared on November 20 before a Ugandan General Court Martial "a military tribunal" in Kampala. He and a colleague, Haji Obeid Lutale, were promptly charged with “security-related offenses” and the unlawful possession of firearms and ammunition, accusations his family and lawyers vehemently deny. The 68-year-old Besigye, a four-time presidential contender and former physician to Museveni, was remanded to the maximum-security Luzira Prison, where he remains behind bars as of May 2025.

The rendition of Kizza Besigye from Kenyan soil blatantly violated international human rights law and the due process safeguards that should govern extraditions. UN Human Rights Chief Volker Türk expressed alarm and called for Besigye’s immediate release, declaring that “such abductions of Ugandan opposition leaders and supporters must stop, as must the deeply concerning practice in Uganda of prosecuting civilians in military courts”. Indeed, trying a civilian before a military court contravenes both Uganda’s constitution and a recent Supreme Court ruling. On January 31, 2025, Uganda’s Supreme Court held that military courts have no jurisdiction over civilians and ordered all such cases transferred to ordinary courts. Rather than comply, authorities and lawmakers maneuvered to sidestep the ruling. In May 2025, Uganda’s parliament passed a controversial bill effectively authorizing military tribunals for civilians, undermining the court decision of the Kabaziguruka V Ag Case. Rights groups condemned this “militarization of justice,” noting that Besigye’s arrest and ongoing prosecution on charges of treachery (treason) that carry a potential death penalty – appear aimed at crushing dissent ahead of Uganda’s 2026 general election.

Besigye’s current plight is the culmination of a long campaign of persecution against him and other Ugandan opposition figures. As the leader of the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) and a perennial challenger to Museveni, Besigye has been arrested countless times over the past two decades. Notably, after the disputed 2016 election, he was charged with treason for symbolically swearing himself in as the “people’s president” spending time in prison and under house arrest for months. More recently, in the 2021 elections, a new opposition under the National Unity Platfrom (NUP) leader, Robert Kyagulanyi (Bobi Wine), mobilized massive youthful support, only to face a violent clampdown: security forces shot dead dozens of protesters, arrested hundreds of opposition supporters, and confined Kyagulanyi to house arrest in the election’s aftermath. A March 2022 Human Rights Watch report documented how, between 2018 and 2021, Ugandan security agencies “unlawfully detained and tortured hundreds of government critics, opposition supporters, [and] peaceful protesters”, often in unauthorized detention facilities commonly known as “safe houses”. Victims described beatings, electric shocks, injections with unknown substances, and other forms of torture and ill-treatment at the hands of soldiers, police, and intelligence operatives. Many were held incommunicado for weeks or months without charge – classic enforced disappearances designed to instill fear. “The Ugandan government has condoned brazen arbitrary arrests, illegal detention, and abuse of detainees by its officials,” HRW’s Uganda researcher Oryem Nyeko stated, highlighting a culture of impunity for security forces.

The persecution of opposition members often goes hand in hand with harassment of their lawyers and family. In Besigye’s case, after his abduction and arraignment, one of his attorneys, Eron Kiiza, was arrested at the court martial for allegedly “shouting” in protest when denied access to his client. Kiiza was summarily tried by the military tribunal for “contempt of court” and sentenced to nine months in prison an extraordinary punishment that Amnesty International called a brazen targeting of a lawyer for defending an opposition figure. Meanwhile, Besigye’s wife, Winnie Byanyima (herself a prominent international official), has vocally rejected the charges, noting her husband “has not owned a gun in 20 years” and decrying the military trial as fundamentally unfair. Despite court orders and public pressure, Museveni’s government has shown no intention of relenting. Besigye continues to languish in detention, denied bail as hearings are repeatedly postponed. His health reportedly deteriorated after a hunger strike in early 2025, which he launched to protest being held illegally under military jurisdiction.

Uganda’s hard line against dissent is driven by the regime’s determination to secure its grip on power at all costs. In recent years, authorities have banned opposition protests, blocked or shut down social media during election periods, and violently dispersed gatherings. In November 2020, for example, spontaneous protests erupted after Bobi Wine’s arrest during the campaign; security forces responded with live fire, killing at least 54 people over two days, according to official figures, and injuring scores more one of the bloodiest crackdowns in Museveni’s tenure. While these killings drew international condemnation, virtually no one has been held to account for the excessive use of force. This impunity for abuses from torture to extrajudicial killings remains the norm. Ugandan authorities typically dismiss reports of torture or disappearances as exaggerated, and instead have intensified tactics such as charging civilians in military courts (as in Besigye’s case) or using sweeping laws (like anti-terrorism or public order acts) to criminalize dissent. Human Rights Watch found that between the 2016 and 2021 elections, numerous detainees many of them young supporters of the opposition were held without trial in military facilities and “disappeared” for periods, only to surface bearing torture scars and terrifying stories of abuse.

What sets the Besigye episode apart is its transnational character. It not only exemplifies Uganda’s disregard for legal norms, but also implicates neighboring Kenya in the violation. At first, Kenyan officials denied any role in Besigye’s kidnapping. But mounting evidence and outcry forced admissions that Kenyan security agencies “cooperated with Ugandan authorities” in what Kenyan opposition leader Martha Karua lambasted as an unlawful rendition. Karua a former Justice Minister now representing Besigye in his Ugandan trial was “completely scandalised” by Kenya’s actions, accusing both Kampala and Nairobi of behaving like “rogue states” in colluding to abduct a protected person on Kenyan soil. “Kenya is admitting to being a rogue state,” she remarked, stressing that such cross-border abductions are “completely outside of the law” and violate Kenya’s own sovereignty and international obligations. Even a senior U.S. senator, Jim Risch, weighed in that Besigye’s abduction “raises serious questions” about key U.S. partners flouting international norms. Despite the criticism, Uganda’s government remained defiant its spokesperson insisted that “arrests abroad” are conducted in collaboration with host countries, effectively acknowledging the practice of transnational repression while attempting to legitimize it. The International Commission of Jurists warned that Besigye’s forced return was “reminiscent of a terrible period in East Africa’s history when state-sponsored kidnappings and cross-border renditions were the order of the day.” For veteran observers, the incident echoes the 1970s-80s era when dictators in Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania routinely cooperated to hunt down each other’s dissidents a trend the region had hoped was consigned to history. Today, Besigye’s fate sends a chilling message to government critics: even fleeing to a neighboring country may not guarantee safety from an ever-more emboldened authoritarian playbook.

Tanzania's Return to Repression: The Authoritarian Continuum

Under the late President John Magufuli (2015–2021), Tanzania underwent one of its darkest periods for civil liberties since the introduction of multiparty politics. Magufuli’s regime earned a reputation for strangling democratic space—banning opposition rallies, censoring media, and jailing critics on flimsy charges. By 2020, as Tanzania headed into a general election, the climate was one of fear and coercion. Human Rights Watch documented that in the weeks around the October 2020 polls, authorities arbitrarily arrested scores of opposition leaders and supporters, suspended critical media outlets, and even used lethal force against civilians. On the eve of the election in Zanzibar, for instance, police fired live ammunition into crowds, killing at least three people. Nationwide, opposition activists were routinely detained; the main opposition party CHADEMA reported up to 300 of its members arrested during the election period. The presidential candidate for CHADEMA, Tundu Lissu, was himself arrested multiple times and saw his campaign severely obstructed. (Lissu had already survived an assassination attempt in 2017, when unknown assailants shot him 16 times—a case that remains unsolved and emblematic of the extreme risks faced by government critics.) International observers and rights groups noted that repression marred the 2020 elections, undermining their credibility. “The Tanzanian government crackdown on the opposition and the press… undermined the credibility of the elections,” HRW concluded, calling for investigations into abuses and an end to repressive practices.

When President Samia Suluhu Hassan took office in March 2021 following Magufuli’s sudden death, there were cautious hopes that Tanzania might reverse course on its authoritarian trajectory. In her initial months, President Samia made gestures of reform—she lifted a Magufuli-era ban on opposition political rallies, met with exiled opposition figures (including Lissu, who had fled abroad after 2017), and allowed some banned newspapers to resume. These steps earned her international praise as a potential reformer in a country that had been labeled “one of Africa’s most repressive states” by the end of Magufuli’s tenure. By early 2023, Lissu felt confident enough to return to Tanzania from exile, signaling renewed optimism for political openness.

However, the reformist glow did not last. By 2022–2023, cracks in the new narrative emerged. In mid-2021, even under Samia’s watch, opposition leader Freeman Mbowe (chairman of CHADEMA) was arrested on dubious terrorism financing charges and spent over seven months in prison without trial, until international pressure helped secure his release in 2022. Other opposition activists continued to face harassment, and old cases from the Magufuli era were not dropped. Then, as the 2025 general elections approached, the ruling establishment appeared to revert to hardline tactics against its challengers. In September 2024, Tanzanian police arrested several opposition members on allegations of unlawful assembly and incitement, reviving memories of the Magufuli-era sweep of dissidents.

The most dramatic turn came in early 2025: the very same Tundu Lissu—now back and gearing up to challenge the ruling party—was charged with treason. The charge stemmed from a 2020 speech in which Lissu had allegedly urged the public to demand electoral reforms and consider boycotting a flawed election. Authorities claimed this amounted to “incitement to rebel” against the state. Lissu’s treason case, which carries a potential death penalty, has become a flashpoint for Tanzania’s human rights record. His court appearances in Dar es Salaam have drawn crowds of supporters chanting “no reforms, no election,” even as heavy security is deployed. Notably, the Tanzanian government has demonstrated a determination not only to prosecute Lissu but to control the narrative and deter external scrutiny.

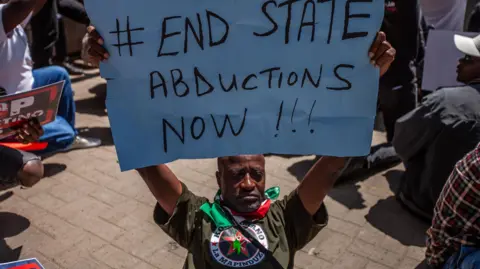

In May 2025, as Lissu appeared in court on politically motivated charges, a group of regional human rights observers and allies traveled to support him. Instead of being welcomed in the spirit of international solidarity and justice, they were met with unlawful arrests, incommunicado detention, and acts of degrading abuse. Among those targeted were Boniface Mwangi, a renowned Kenyan activist, and Agather Atuhaire, a Ugandan journalist and lawyer both of whom were detained and subjected to horrific torture, including sexual assault, before being deported.

Their ordeal began in Dar es Salaam, where they were seized by plain-clothed security agents, blindfolded, and taken to a secret location. Mwangi was tied upside down, sexually assaulted with foreign objects, and ordered to praise President Samia Suluhu Hassan during his torture. He was smeared in excrement, beaten on the soles of his feet, and repeatedly threatened with circumcision and death. Atuhaire suffered equally horrific abuse: she was stripped, beaten until she could no longer walk, and violated with objects by officers who filmed the ordeal. Her body was smeared in filth, and her screams echoed through the chambers of her captivity. Painkillers were administered excessively to keep her functional not for relief but to mask the evidence.

Despite their severe physical and psychological injuries, both survivors have spoken out publicly. In a powerful press conference held in Nairobi on June 2, 2025, Atuhaire declared: “I am not ashamed. They should be. I will speak until there is justice.” Mwangi, echoing this call, said, “We were tortured for standing in solidarity. This must not happen to anyone else.” Both activists confirmed that the torture was systematic, filmed for blackmail, and directed by high-level Tanzanian security officials.

The targeting of foreign observers didn’t end with them. On May 18, 2025, Kenyan politician Martha Karua, former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, Vocal Africa CEO Hussein Khalid, and activist Hanifa Adan were denied entry and deported from Tanzania. These actions drew immediate rebuke. “It’s the actions of two rogue states,” Karua remarked, referring to Kenya and Uganda’s history of repression, now mirrored by Tanzania.

A coalition of East African human rights groups, along with Amnesty International and the U.S. State Department, condemned the incident and demanded independent investigations. Yet Tanzanian authorities remain silent. President Samia Suluhu Hassan, without addressing the abuses, doubled down on her administration’s stance, warning on May 22 against foreign “meddling,” asserting that outsiders should not “invade and interfere in our affairs.” This rhetoric, paired with the treatment of Lissu’s trial as a national security matter, suggests a regime deeply intolerant of dissent.

What happened to Boniface Mwangi and Agather Atuhaire was not an isolated abuse—it was a signal. A signal that cross-border repression in East Africa is becoming normalized, that foreign solidarity can be criminalized, and that torture remains a tool for silencing opposition. Their testimonies stand not just as records of pain, but as beacons for accountability. In their courage, the region must find its conscience.

The continuing crackdown in Tanzania extends beyond marquee opposition leaders to the grassroots of civil society. Under Magufuli, journalists, bloggers, and NGO workers were arrested, media outlets shut down, and draconian laws (like the Cybercrimes Act and restrictive media regulations) were used to silence critical voices. Under Samia, some media freedoms have improved on paper, but many restrictive laws remain in place and self-censorship is widespread due to the legacy of intimidation. Meanwhile, certain groups have faced unabated persecution—for instance, the LGBTQ community, which saw intensified official hostility from 2016 onward, continues to be marginalized and harassed by authorities. As the 2025 elections near, rights advocates fear an escalating climate of fear akin to 2020, unless strong safeguards are implemented. The arrest of young CHADEMA activists in late 2024 for simply holding internal meetings suggests that security forces still view any political organizing as a threat to be quashed preemptively. The pattern is clear: despite a brief hopeful interlude, Tanzania has largely returned to repressive form, using the judicial system to pursue trumped-up charges (like treason or sedition) against opposition leaders, and using police powers to preempt or punish any form of public dissent. This resurgence of repression dashes hopes that Tanzania might chart a new course and instead echoes the authoritarian tendencies of its regional neighbors.

Kenya: Democratic Façade and Collusion in Repression

Kenya is often considered an outlier in the region a multiparty democracy with a vibrant civil society and a history of alternation of power between political parties. Over the past decade, Kenyans have enjoyed greater freedom of expression and protest than citizens of Uganda or Tanzania. However, Kenya is not immune to human rights abuses or authoritarian backsliding, especially when authorities feel threatened by mass dissent. Additionally, recent events have put Nairobi in the spotlight for abetting the repression orchestrated by its neighbors, revealing a troubling willingness to sacrifice principles for political expediency.

Internally, Kenyan security forces have at times responded to opposition protests and perceived unrest with excessive and lethal force, drawing condemnation from rights monitors. A stark example came after Kenya’s own contentious 2017 elections: when opposition supporters took to the streets accusing the government of election fraud, police cracked down violently in some areas, and dozens of people were killed or injured in the post-election unrest (according to human rights organizations and a government commission of inquiry). Fast forward to 2023-2024 under President William Ruto’s administration, and we see a similar pattern. In mid-2023, the opposition led by Raila Odinga organized nationwide protests (popularly termed “Maandamano”) against the high cost of living and new tax proposals. Those demonstrations continued into 2024, culminating in July 2024 protests against a controversial Finance Bill. Instead of protecting the right to peaceful assembly, Kenyan authorities launched what Human Rights Watch described as an “ongoing deadly crackdown on protesters”, marked by abductions and police brutality.

According to a detailed November 2024 HRW investigation, between June and August 2024 Kenyan security units abducted, tortured, and even extrajudicially killed individuals they identified as leaders or instigators of the anti-government protests. Police and intelligence officers often in plainclothes and concealing their faces hunted down activists weeks after the protests, driving unmarked cars with changing license plates to avoid detection. Victims were seized from their homes, offices, or off the street, frequently by agents of the Directorate of Criminal Investigations and other special units. They were then held in unofficial detention sites (including forested areas and abandoned buildings) where they were brutalized while denied access to lawyers or family. Witness testimonies gathered by HRW are harrowing: detainees recounted being beaten with clubs, rubber whips, and gun butts; some had their nails or pubic hair pulled out with pliers during interrogations. Nearly all reported being deprived of food, water, and basic dignity “I was made to sleep on a cold concrete floor with my hands bound…They did not give us food for three days,” one 28-year-old protester recalled of his ordeal in a secret cell. Others were threatened with death or asked to pay bribes for their freedom. At least several protesters were killed or disappeared: families described seeing their loved ones shot dead by police only for the bodies to be hauled away, or relatives bundled into vehicles never to be seen again. In one case, a Nairobi man saw masked men believed to be police violently kidnap his brother, who remains missing months later. These accounts underscore that enforced disappearances and torture tactics typically associated with autocratic regimes have been employed in Kenya as well, severely tarnishing the country’s human rights record.

Kenyan officials initially defended the tough response by labeling protesters as rioters and even “terrorists” President Ruto infamously referred to the storming of parliament grounds by angry youth on June 25, 2024 as an “invasion” tantamount to treason. But human rights organizations blasted this rhetoric, noting that it appeared to give security forces a green light to use unlawful deadly force and abductions to terrorize government critics. “The authorities should end the abductions… and ensure prompt investigation and prosecution of security officers credibly implicated in abuses,” urged HRW’s associate Africa director Otsieno Namwaya. Instead of upholding the rule of law, Kenyan police and intelligence units seem to have operated as if above the law, believing that crushing dissent was necessary to protect the state. This erosion of the rule of law in Kenya is particularly dismaying given the country’s status as East Africa’s biggest economy and a regional hub for human rights activism. It reveals that even in a formally democratic system, old habits of security force impunity die hard – a legacy from the one-party era and the “war on terror” years that saw abusive crackdowns – unless strong institutional checks are in place.

Even more disturbing has been Kenya’s role as a willing partner in transnational repression, effectively outsourcing its security apparatus to aid neighboring autocrats. The kidnapping of Kizza Besigye in downtown Nairobi in November 2024 is the most prominent example, but it was not an isolated case. As mentioned, Kenya quietly deported 36 Ugandan opposition supporters in July 2024 members of Besigye’s FDC party who had fled to Kenya handing them over to Ugandan authorities who then charged them with terrorism-related offenses. Kenyan authorities also in October 2024 deported four Turkish nationals (alleged critics of Turkey’s government who had refugee status) back to Ankara, an action that drew sharp criticism from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. These incidents point to a pattern whereby Kenyan security agencies collude with foreign governments, disregarding Kenya’s obligations under international law to protect asylum seekers and not to return people to countries where they face persecution. Local and international rights groups have decried this trend: a joint petition by Kenyan civil society organizations in early 2025 urged Parliament to acknowledge that “abductions and renditions…constituting crimes under international law have been committed in Kenya” and to take urgent action to end such practices. Amnesty International and others warned that Kenya is becoming a hotspot for cross-border repression noting cases of dissidents from Ethiopia, South Sudan, Rwanda, Turkey, and Uganda being targeted on Kenyan soil in recent years. This not only endangers activists who once considered Kenya a safe haven, but also flagrantly violates Kenya’s own constitution and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which guarantees personal liberty and security.

The Besigye case unleashed a storm of criticism within Kenya as well. The revelation by Kenya’s own Foreign Affairs Ministry that it “cooperated” with Uganda’s plot led to accusations that the Kenyan government traded away national sovereignty and the rule of law for regional political expediency. Observers suggested that Nairobi’s complicity was driven by a desire to maintain cordial relations with Museveni a powerful neighbor or possibly by an undisclosed quid pro quo within EAC security cooperation frameworks. In a television interview, Kenya’s Foreign Minister defended the action by saying Uganda is a “friendly nation” and that Besigye was not officially seeking asylum in Kenya (implying that if he had, the situation “maybe…would have been different”). Such justifications rang hollow to Kenyan human rights defenders. They argue that Kenya’s authorities had a legal and moral duty to protect Besigye – or at minimum to follow formal extradition procedures – rather than facilitate a kidnapping. By betraying an opposition figure to a foreign state, Kenya set a dangerous precedent and raised fears among its own dissidents that they could face similar fates. As Karua starkly put it, “It’s the actions of two rogue states” – a damning indictment of both Uganda and Kenya for their joint operation. Under public pressure, Kenya announced an investigation into “how [Besigye] was spirited out of Nairobi”, but few expect senior officials to be held accountable. The fallout has left Kenya’s reputation stained, just as much as Uganda’s, and shined a light on an uncomfortable reality: the EAC’s most democratic member is, behind the scenes, enabling authoritarian abuse.

Transnational Repression:

The threads linking these country cases reveal a regional pattern of repression that ignores national boundaries. Within the EAC, governments are increasingly acting in concert to quell dissent beyond their own jurisdiction, effectively crafting an informal alliance against opposition activists. The abduction of Besigye in Kenya and the arrest of activists in Tanzania are part of what Amnesty International calls a “growing and worrying trend of transnational repression”, where East African governments violate human rights beyond their borders to target critics. Kenya’s cities, once considered neutral ground, have become hunting grounds for multiple security services: Ethiopians, South Sudanese, Rwandans, Ugandans, and others have reportedly been surveilled, abducted or unlawfully extradited from Kenya with the collusion of Kenyan authorities. This trend blatantly flouts international law including the 1951 Refugee Convention and the UN Convention against Enforced Disappearance – and undermines the integrity of the EAC as a community of nations that should uphold shared standards. If an opposition member from Country A cannot seek refuge or even travel to Country B without risk of illegal rendition, the regional integration project itself is tainted. Civil society groups across East Africa have begun to join forces, recognizing that repression in one country is increasingly entwined with repression in another. After Besigye’s abduction, a broad coalition of human rights organizations from Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania (as well as pan-African bodies) issued a joint statement demanding his release and an end to cross-border abductions. They planned joint protests such as a march to the Ugandan High Commission in Nairobi to signal that East African citizens reject the use of their countries as trading grounds for political prisoners.

Martha Karua’s charge that Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania are “collaborating to oppress the citizens [and] violate their rights” rings true when examining these incidents. The coordination can be tacit or overt: Kenyan police quietly handing fugitives to Ugandan operatives, or Tanzanian and Ugandan officials exchanging intelligence on exiled dissidents. There is also a legal convergence: abusive laws and practices are being mirrored across borders. All three countries have, for example, misused treason or terrorism charges to imprison opposition leaders (be it Besigye, Lissu, or Kenyan protest organizers labeled as “saboteurs”). All three have seen military or special courts being used to try civilians in sensitive political cases a tactic meant to circumvent the independence of the civilian judiciary. And in all three, we see attempts to legalize or whitewash repressive measures: Uganda’s bill to allow military trials for dissidents, Tanzania’s laws restricting media and foreign scrutiny, and Kenya’s public order rhetoric casting protesters as traitors all serve to legitimize crackdowns that breach basic rights.

This regional pattern has not gone unnoticed by international observers. The United Nations, the African Union’s human rights bodies, and foreign allies have raised alarms about the deteriorating human rights climate in East Africa. UN officials have called for investigations into abuses for example, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights urged probes into Tanzania’s election-related violence in 2020 and condemned Besigye’s kidnapping in 2024. However, such exhortations have often been met with defiance or lip service. East African regimes are adept at paying lip service to human rights while cracking down in practice. President Samia’s insistence that her government respects human rights, even as she jails opponents, and Kenya’s stated commitment to rule of law, even as it engages in extrajudicial renditions, exemplify this duplicity. Within the EAC itself, there is currently no robust mechanism to enforce human rights compliance. The EAC Treaty articulates respect for human rights, rule of law, and democracy as core principles, and the East African Court of Justice has in the past asserted that human rights are integral to the community’s objectives. Yet, enforcement is weak Partner States have been slow to grant the EACJ direct human rights jurisdiction, and rulings (such as one rebuking Burundi for rights violations) have had limited impact. This leaves accountability largely in the hands of national institutions, which, as seen, are often compromised or overridden in political cases.

Conclusion

Across Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya, the past decade has illustrated in stark terms the high cost of freedom for those who dare dissent. Speaking truth to power in these countries can lead to arbitrary imprisonment, physical harm, or even death. Activists and opposition figures have been treated as enemies of the state – kidnapped off streets, beaten and tortured in secret detention, dragged before military courts, or prosecuted on trumped-up charges meant to silence them. The pattern from 2015 to 2025 is depressingly consistent: whenever incumbent regimes feel their grip on power threatened – whether by an electoral challenge, public protests, or critical voices – they respond with repression that flouts their own laws and international standards.

The incorporation of cross-border repression adds a new and dangerous dimension. The November 2024 abduction of Dr. Kizza Besigye in Nairobi, and the collusion of Kenyan authorities in that act, demonstrate that no opposition figure in East Africa can assume safety simply by crossing a border. A dissident from one EAC country may be viewed as a political pawn by another, to be exchanged or expelled in the interest of regime solidarity. This under-the-table cooperation among East African governments undermines the very premise of regional integration instead of a community bound by shared values and the free movement of people, we see a cabal of leaders shielding each other from accountability and trading away the rights of their citizens. As one Kenyan commentator lamented in the wake of Besigye’s kidnapping: “What is the value of our national sovereignty if our government can conspire to abduct someone on our land at the behest of a foreign regime?” The sovereignty of the people, which is foundational to democracy, has been subjugated to the convenience of those in power.

Yet, even in the face of this repression, brave activists, lawyers, and ordinary citizens across East Africa continue to push back. Their courage – whether it’s staging protests in Kampala, filing court petitions in Nairobi, or monitoring trials in Dar es Salaam – keeps the flame of freedom alive. International human rights organizations and local NGOs are increasingly joining forces, as seen in joint statements and petitions, to demand adherence to the rule of law and the immediate release of political prisoners. They call not only for freeing individuals like Besigye and Lissu, but for systemic changes: independent investigations into abuses, abolishing the use of military courts for civilians, repealing draconian laws, and holding perpetrating officials to account. These are steep challenges in countries where the judiciary and oversight institutions are often under executive sway. Nevertheless, domestic and international pressure has yielded some successes for example, the release of Tanzania’s Freeman Mbowe in 2022, or the quashing of some sham charges in Kenya proving that sustained advocacy can make a difference.

In conclusion, the “price of freedom” within the EAC remains perilously high. As of May 2025, Dr. Kizza Besigye sits in a prison cell for daring to oppose a president; Tundu Lissu faces a death-penalty charge for demanding free elections; and Kenyan youth bear scars from torture for protesting economic policies. These personal tragedies reflect a broader assault on democratic principles that, if left unchecked, threatens to reverse the gains of the last 30 years in East Africa. The EAC’s founding treaty envisions respect for human rights and the rule of law as fundamental to the community. It is imperative that EAC member states be held to these commitments. Ending unlawful arrests, torture, and transnational repression is not just a moral imperative but a legal one – under both African and international law. If East African leaders continue on the current path, they risk transforming the region into a place where integration is driven by the mutual export of fear rather than the free exchange of ideas and people. The true measure of integration should be how easily citizens can travel for trade or study not how easily security agents can hunt down those citizens across borders.

Ultimately, the fate of freedom in the EAC will depend on the courage of those who stand up to tyranny and the pressure that citizens and international partners can bring to bear on regimes that have grown accustomed to using brute force. The stories of Besigye, Lissu, and many unnamed activists serve as both a warning and a rallying cry. The price of freedom is steep – but with solidarity and persistence, East Africans may yet ensure that freedom prevails over fear.

References

Amnesty International Kenya – Joint Statement: Ugandan authorities must immediately release Dr Kizza Besigye, Hajj Obeid Lutale, Eron Kiiza and others unlawfully detained (Press release, 18 Feb 2025).

Amnesty International (Urgent Action) – Uganda: Opposition politician charged after abduction – Kizza Besigye (28 Nov 2024).

Reuters – Kenya investigating how Uganda opposition figure was 'abducted' (21 Nov 2024).

Reuters (AFP report via Citizen Digital) – Kenya slammed as 'rogue' state over Uganda opposition kidnap role (22 May 2025).

Reuters – Tanzanian police arrest (and deport) foreign activists supporting detained opposition leader (20 May 2025).

Human Rights Watch – Uganda: Hundreds ‘Disappeared,’ Tortured (Report, 22 Mar 2022).

Human Rights Watch – Tanzania: Repression Mars National Elections (Report, 23 Nov 2020).

Human Rights Watch – Kenya: Security Forces Abducted, Tortured and Killed Protesters (News release, 6 Nov 2024).

Jurist – Rights groups urge Kenya government to end abductions and renditions (News report, 27 Feb 2025).

OHCHR – Comment by UN Human Rights Chief Volker Türk on abduction of Ugandan opposition politician (Geneva, 21 Nov 2024).

East African Community Treaty – Article 6(d), Fundamental Principles (1999): good governance, democracy, rule of law, and protection of human rights.

The Guardian – Tanzania: Restrictions and repression ahead of elections (27 Oct 2020).

Comments